Wastewater epidemiology, not exactly a household term, has moved into the mainstream media throughout the pandemic. Just last week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention touted wastewater and sewage as ‘the latest public health tool providing critical information on COVID-19 trends.’ From MIT to Kuwait, scientists are relying on epidemiology to offer insights into public health.

On the most basic level, the process involves tracking consumption or exposure to chemicals and pathogens by measuring chemical or biological entities in municipal wastewater flowing into a sewage treatment plant catchment. Simply put, studying a community’s human waste reflects the population’s overall health. This is not a new practice—look no further than individual analyses of Olympic athletes’ urine samples for drugs. This just happens to be at scale and more efficient in understanding the ebb and flow of a more widespread concern (e.g., pandemic).

Wastewater based-epidemiology (WBE) allows us to track not just COVID, but specific variants, letting public officials know how quickly the Omicron or Delta or whichever variant du jour is transmitting through a population. This kind of tracking has huge implications today and going forward, enabling the monitoring of other diseases, drugs, and contaminants in water including PFAS, lead, legionella, arsenic and more. It could also be used to understand a community’s patterns, including dietary habits and pharmaceutical usage—both of which have potential commercial value.

The CDC’s estimates suggest between 40% and 80% of people with COVID-19 shed viral RNA in their feces, making wastewater and sewage an important opportunity for monitoring the spread of infection. What started as a grassroots effort by academic researchers and wastewater utilities has quickly become a nationwide surveillance system with more than 34,000 samples collected representing approximately 53 million Americans. Currently, the CDC is supporting 37 states, four cities, and two territories to help develop wastewater surveillance systems in their communities.

By putting the CDC’s data of more than 400 testing sites around the country into Bluefield’s own data visualization tool, we can observe a nearly 50% increase in positive wastewater samples nationally from June 2021 to September of 2021 with current hotspots in West Virginia and Wisconsin.

But How Do They Do It?

Technology companies, once considered “start-ups,” from GoAigua to Biobot are moving to the forefront of this space by promoting wastewater-based epidemiology capabilities. Through its wastewater intelligence platform, Kando uses IoT, original algorithms and artificial intelligence technologies to enable utilities and municipalities to “gain insight and control over their wastewater networks” by detecting pollution anomalies and blockages.

From university campuses to schools to prisons, this technology is being employed throughout the world. The Netherlands used wastewater-based epidemiology to monitor Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. While real-time analysis is not possible at this point, universities have been able to save 1 to 2 days by doing analysis directly in their own labs, instead of having to ship samples to a lab. As a result, wastewater-based epidemiology has been a crucial indicator informing schools’ re-entry policies and timelines, and monitoring the overall situation when students returned to classes.

Preliminary results demonstrate the technology’s ability to pinpoint specifically affected neighborhoods and hotspots. At a very targeted scale, it can lead to more concrete actions: isolating a dorm or closing a jail’s specific building. It also provides a way to monitor the health of populations that are less likely to get tested. San Diego used wastewater epidemiology in its schools in low-income communities because people were afraid of getting tested and had jobs, like cashiers and factory workers, that made them more likely to get infected.The growing resources and strategic investments directed towards the precise and timely identification of pathogens in water and wastewater, at a neighborhood, and even building level, is groundbreaking for

What Does This Mean for the Water and Wastewater Industry?

Wastewater has historically taken a backseat in the water industry. But what if our wastewater could literally save our lives? Will investment in smart sewers (which often takes a backseat to water infrastructure via funding and more) finally take off? Let’s hope so.

This sudden reliance on wastewater systems as a critical source of community intelligence has gotten utilities, communities, and policymakers thinking about what other data or information our sewer systems can provide. This could drive greater investment in smart sewers and prompt us to re-think how we engineer and design sewers to build in access points for sensors, IoT, and more.

This could drive greater investment in smart sewers and prompt us to re-think how we engineer and design sewers to build in access points for sensors, IoT, and more.

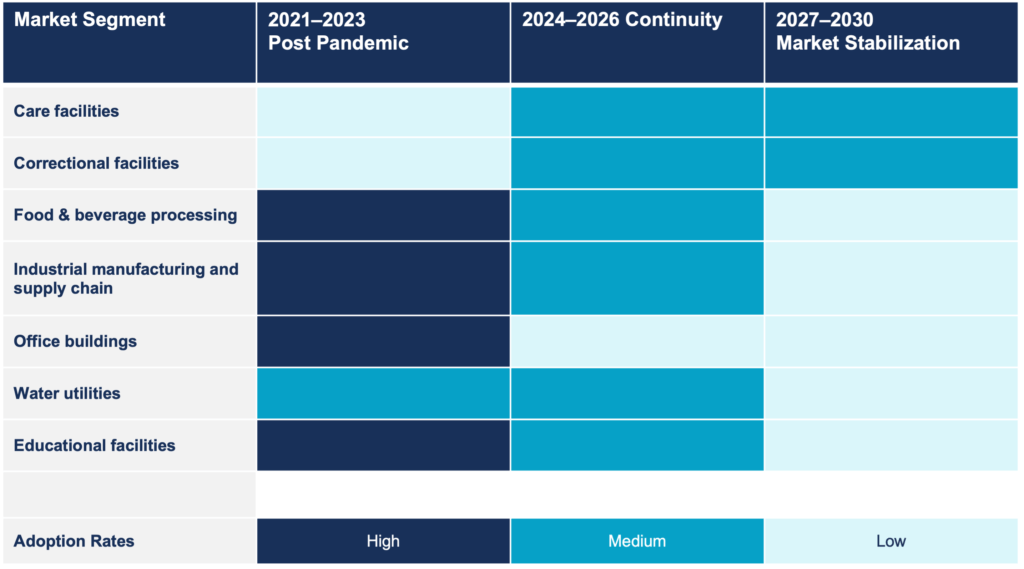

As we move into this next phase of the pandemic following the Omicron wave, Bluefield anticipates multiple applications for WBE already taking root in several sectors. In the short term we see high adoption driven by a strong business case at private companies and universities. But several segments (e.g., food & beverage producers) are highly dependent on specific transmission conditions, facility types, and regulations. As such, the role of utilities as test beds is key for wastewater monitoring.

Bluefield Anticipated Adoption of WBE for COVID-19 Detection, by End User Segments